Such rivers are important in setting the relief of many mountain ranges, and hence the results have important implications for how local climate and climate change interact with topography.

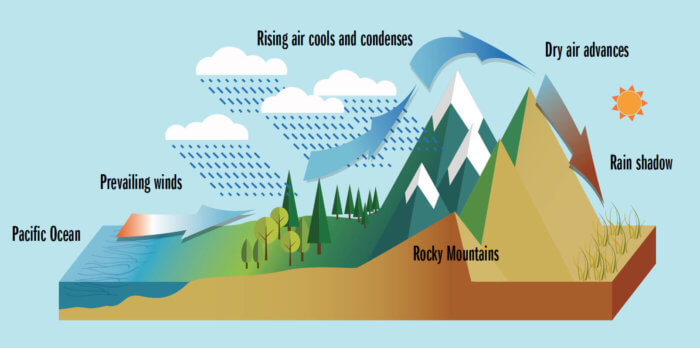

This paper explores how patterns of precipitation affect the relief along a bedrock river channel. Tucker and Bras and Snyder studied the impact of storm frequency on river profile evolution, and a few landform evolution models have implemented simple orographic rules for precipitation, but the consequences of the implied feedback have not been explored in depth and the representation of climate tends to be crude. Given that a river's (or a glacier's) power to incise into rock is controlled by the conversion of precipitation into river discharge (or ice flux), and that a fundamental feature of mountain climates is strong orographically driven gradients in precipitation, there is a potential for an interaction between relief development and precipitation patterns. In actively uplifting mountain ranges the relief, and ultimately the rate of landscape exhumation, are set by river and glacier incision into bedrock. Although these studies addressed the potential for interactions between climate and relief development, relatively little attention had been paid to the interaction between orographic precipitation and relief. Montgomery and Greenberg showed how in a real landscape excavation of valleys could substantially increase the height of local mountain peaks. argued that there is little potential for enhanced river incision to substantially increase relief in a landscape with landslide-dominated threshold hillslopes. On the basis of a model of a steady state river profile, Whipple et al. and Montgomery showed that the erosional deepening of valleys, which create relief, could account for at most a roughly 25% increase in the height of mountain peaks. They argued that evidence for increased late Cenozoic rock uplift simply recorded the isostatic uplift of mountain peaks in response to enhanced excavation of valleys. Molnar and England offered the opposing hypothesis and argued that evidence for such uplift primarily reflected greater rates of exhumation and isostatic rebound due to higher erosion rates accompanying climatic deterioration. They suggested that enhanced chemical weathering of exposed rock surfaces in uplifted mountain ranges plays an important role in reducing the long-term level of atmospheric CO 2 and hence that tectonic uplift may have led to the onset of a glacial climate. noted that the long-term cooling of climate over the last five million years coincides with evidence for increased mountain uplift around the globe. Much of the discussion of the relation of climate to landscape evolution has centered on the role of relief development. While atmospheric scientists have long understood that the largest mountain ranges such as the Himalayas-Tibetan Plateau and the Rocky Mountains, cause hemispheric-scale changes in atmospheric circulation, and hence in the position of the jet stream and storm tracks, only recently has it been recognized that climate, in turn, influences the form and evolution of large mountain ranges. Among geomorphologists, interest in the influence of climate variability has been largely overshadowed by interest in the competition or relative balance between erosion and uplift in mountain range evolution. The structure and form of landscapes is ultimately controlled by the interplay between tectonics, erosion, and climate.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)